Strengthening Families

Keynote address, 5/25/96

By Rev. Thomas F. Brosnan

Catholic Charities USA

1996 National Maternity and Adoption Conference

San Antonio, Texas

April 24-27, 1996

This presentation is entitled Strengthening Families. Through references to history, literature, film and personal experience I will attempt to offer some suggestions on how adoptive families might fight the subtle and not-so-subtle forces which seek to weaken and destabilize the family unit. I will suggest that strength is born of the acknowledgment of truth, specifically an acknowledgment of truth about the experience of Loss and the nature of Belonging.

By way of introduction my name is Tom Brosnan. I am a Roman Catholic Priest of the Diocese of Brooklyn, New York, where I presently live and work with Korean Catholics. I am no psychologist, pastoral counselor, or social worker; in other words, I’m no expert. My remarks come from my experience concerning my own adoption and that of other adopted persons, birth parents, and adoptive parents with whom I have worked over the past 15 years. This presentation is, I suppose, a “confession” of sorts regarding my journey of discovering who I am; a process which, I would suggest, is the vocation of every human being, adopted or not.

Permit me to begin with a little background. In 1952 a young woman of 25 was living in a boarding house connected with the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, Maryland. She was not a music student like her roommate or the rest of the inhabitants of the house, but was invited to stay there because there were few female boarders. She met a music student from Toronto, and they fell in love. She realized she was pregnant after her boyfriend had returned to Toronto at semester’s end. She visited, she pleaded, but he said he could not, he would not marry her. Meanwhile another student from Peabody, a gallant young man from Virginia, who knew she was pregnant offered to marry her. The other students, not knowing she was pregnant, had a bridal shower for her in their boarding house. Within a few weeks however she informed her friends that they decided not to marry. Becoming desperate the young woman told her older brother she was pregnant with no hope of marrying. The brother, a Jesuit priest , arranged for her to go to New York to deliver and relinquish the baby for adoption. The priest, the boyfriend, the gallant Southerner and her loyal roommate, Sophia, were the only ones who knew of her pregnancy. She delivered her child on January 10th 1953 at Misericordia Hospital, then located in Manhattan, and immediately relinquished the boy to adoption. He waited in a foster home for six months and was eventually adopted by a couple from Brooklyn where he lived with them and his adoptive mother’s parents in a small row house in Flatbush.

My parents told me I was adopted when I was 12, though I can remember knowing since I was 5. We never talked about adoption, yet it seems to me these many years later that adoption, with all its cumbersome baggage, was the air we breathed. We never acknowledged to each other the truth about the loss each of us suffered. We were, I believe, victims of the closed adoption system which exerts an extraordinarily powerful hold on all members of the triad. It is a cruel task master and demands untold sacrifices. It is merciless in its destructive power. Like the razed Berlin Wall that divided a city for a generation, like the dismantled statues of Lenin across the Russias, I pray for the demise of the closed adoption system. And I offer these words in the hope to effect that outcome by alerting you who are adoptive parents, adoption specialists, social workers and clergy to the dangers that secrecy and lies can wield on the family.

I love the movies. It’s one of the few places I lose my self-control and permit myself to feel those difficult emotions which the experiences of Loss and Belonging evoke. One of my favorite films of all time is Cinema Paradiso, an Italian film of a few years ago about a fatherless young boy from a small Sicilian town who befriends the movie-house projectionist. The boy learns to love movies while learning to love the older man who teaches him so much. When he is 18 he joins the army and we see him standing with his mother and sister at the train station waiting for the good-byes to end. The old man is there too. He whispers in the boy’s ear: “Go, and never, never come back.” The boy obeys. He goes to Rome and becomes a famous film director. He calls his mother now and then but keeps his promise never to return to his hometown. Then, the old man dies, and the mother leaves a message on the son’s answering machine telling him the day and time of the funeral. “You know he’ll never come back,” the skeptical sister tells the mother. But, he does.

On the day of his return the camera is focused on the mother as she sits in a rocker, nervously knitting. Slowly the camera closes in on the knitting needles, deftly moving back and forth twining yarn and space. The camera focuses on her wrinkled hands and the long needles when in the background we hear a car pull up on the gravel path. Suddenly the hands stop, the woman quickly stands, unconsciously catching a piece of the yarn on her dress. The camera stays focused on the yarn as it unwinds with every step the mother takes toward the door. Then we hear the car door slam and the yarn ceases to unravel. We know without a word being spoken, or any visual image given besides the unraveling yarn, that mother and son have embraced after many lost years.

With this simple yet beautiful image I wish to remind you of something you already know: that the experience of Loss and the need to Belong are universal human experiences. But none of us likes to face the pain of Loss, and we don’t like to be reminded of it in others. When we are reminded, our immediate reaction is to make it go away, to lessen its obvious import to the person, to hopelessly put a mere bandage on what is doubtless a gushing wound.

The Catholic Bishops of the United States have done just that in their recently published Book of Blessings. Among the many rituals is one entitled “Blessing for Parents and an Adopted Child”. The prayer begins: “It has pleased God our heavenly Father to answer the earnest prayers of (this couple) for the gift of a child…” Despite the feeling of joy the words are meant to instill there remains the unasked question, have the events which preceded this adoption ritual, namely the relinquishment of the child by his mother, has that also pleased God? What is missing is any reference to what has had to have taken place in order for this joyful blessing to occur. There is no mention, no acknowledgment of Loss, of the relinquishment that had to have occurred in order for the adoption to have taken place.

Although difficult, it is essential to acknowledge this fundamental truth about the experience of Loss in adoption. It is not easy, however, and it is not a one-shot deal. It will have to be acknowledged at different times during the adoptee’s maturing process, but I believe it to be essential in the building of strong healthy families. Acknowledging truth about Loss means first of all to give up the lies about what actually happened. It means giving up myths like the chosen baby story so many adoptees were told. It means to accept the events as are known, not fabricating explanations which we think might lessen the blow. You know what I mean: like the “your parents were killed in a car crash” story, intended to save the adoptee from the truth which we presume to be far worse: a truth like “your parents weren’t married; or, your mother was raped; or even, you’re the product of incest.” If the adoptive parents truly have the best interest of their child at heart, I would suggest that the truth is the only choice they really have in attempting to do what’s best for their son or daughter.

“There is no truth existing which I fear,” Thomas Jefferson once wrote, “or (that I) wish unknown to the whole world.” Another Thomas, many centuries prior to Jefferson, placed truth at the heart of what it means to be a human being. “For (Thomas) Aquinas, the most decisive human trait is that human beings are truth-seeking animals, moved by love for the truth (come what may)…So inherent is this drive for the truth in human nature that it is an imperative…to address a human being in any lesser mode is to do his nature violence.”

As H. David Kirk explained in his ground breaking book on adoption, Shared Fate, published near 30 years ago, there is at least one condition that each member of the adoption triad shares, and that is the experience of Loss. Acknowledging the truth about Loss is the beginning of mutual respect and love.

There’s a beautiful scene at the end of James Joyce’s short story, “The Dead.” Gabriel and his wife Gretta, married a number of years, have attended a dinner party. It’s time to leave and Gabriel is about to call his wife whom he sees at the top of the stairs. Her expression seems melancholy as she listens to the music coming from the next room. Gabriel knows that something profoundly important is taking place within Gretta at that moment. Observing her from the shadows kindles a renewed passion in Gabriel, for he assumes that he is the cause of her wistful look and tearful eye. Later in their hotel room Gabriel is keen on renewing that passion. He confidently asks Gretta what she was thinking about when he saw her as she listened to the old Irish ballad. It is then that Gretta breaks down and begins to sob uncontrollably. She tells her bewildered husband how long before she met him she was courted by a young man named Michael Fury who sang that same ballad to her beneath her window in the drenching rain the night before she was to leave for a convent school. Young Michael Fury caught his death that night, and she knew he died for love of her. This poignantly sad yet beautiful memory was Gretta’s, but it was not Gabriel’s. The cold reality that Gretta had a history before him is like a slap in the face to the middle-aged Gabriel. It was the tune of the ancient ballad that triggered the memory, and Gabriel realized he had no right to transgress such a sacred place.

Not all, but many adoptive parents, come to the adoption process through the Loss we call infertility. Whether couples decide to adopt when they are first diagnosed, or whether they come to that decision only after they have endured the horrors and humiliations of the fertility clinics, once they decide to adopt they have acknowledged the terrible reality that they will never have their own children. The decision to adopt marks the moment they give up their dream of seeing “flesh of their flesh and bone of their bone.” What the infertile couple needs to do is acknowledge that the choice to adopt is their second choice. To admit to themselves that if they had their way adoption would most likely not be a part of their lives. They choose to adopt because there is no other way to become parents.

Acknowledging the truth of Loss is also a part of the birth parents’ lives, especially the mother. I believe there is no closer relationship than a mother and her unborn child. Perhaps you saw the movie Losing Isaiah. Whether or not you liked the scenario, perhaps you would agree with me that even a crack-addicted woman feels that powerful bond with her child. The act of relinquishment is so wrenching an event that young women have told me that they chose to abort their babies rather than relinquish them to adoption. Some of us may judge this to be the height of selfishness, but I wonder if there is not some instinctual response involved in making that drastic decision. No matter what the reasons for relinquishment might be, the emotional response to the act of relinquishment is analogous to abortion, an unbloody abortion if you will, but as one prominent psychiatrist has written, “a psychological abortion” nonetheless.

Maybe you remember the scandal that broke a few years back about the Irish Bishop, Eamon Casey, who fathered a child some twenty years previous with a young American woman named Annie Murphy. Annie’s family had sent her to the bishop to straighten out her life but she ended up having an affair with the bishop and getting pregnant. The bishop arranged for her to go to a home for unwed mothers. When the time for delivery came they had a heated argument. Annie told the bishop she wanted to keep their child. The bishop was furious and said she must give the baby up for adoption. “The child was a mistake,” Annie remembered the bishop saying. “He made it clear, ” she said, “that through the (relinquishment) of the child she would be cleansed.” Thus the bishop believed, as do many religiously-inclined people, that relinquishment is tantamount to the purifying fires of purgatory – a notion I would suggest not far removed from the response of those young women who chose abortion over adoption. There is, of course, another possible reason for the bishop’s insistence on relinquishment. Once placed in the closed adoption system, his son would not be able to identify the bishop as his father.

In my biased opinion the greatest Loss is suffered by the adopted person. I want to make it very clear, however, that adoption may indeed be in many, many cases a wonderful blessing for all involved. It may indeed be the only merciful solution to a seemingly impossible situation. Adoption can be one of the noblest of human achievements, but for the adopted person it is always, always the result of a tragic loss. I am not suggesting that problems within the adoptive family are the result of any lack of love on the part of parents, but simply saying that we must acknowledge the truth and not believe the false premise, the myth, which suggests that love conquers all. Because love does not conquer all, love can not , love should not. “Love can neither eradicate biology,” as one writer-adoptee has put it, nor can love alter events which have already occurred. Let’s not pretend that love can or should.

Adoption is a life-long process and it is at times hard work. The adoptive parents must acknowledge the truth of their infertility not only when first adopting, but years later when their child enters puberty and they begin to witness his or her sexual awakening with all its potential fecundity. They must face it each time their adoptive children have children. Adoption can make an infertile couple into the greatest of parents, but it can never make them fertile.

Adoption as relinquishment is a life-long process for the birth mother. I’ve met a number of birth mothers who have never had any more children; and others, like my mother, who had one child every year, year after year. Some birth mothers feel so guilty, it has been observed, they punish themselves by suppressing their fertility, while others seek to replace what was lost.

For the adoptee, life is adoption. I think this is true whether an adopted person admits it or not. There is always either an active curiosity about where you came from or a strong denial of any desire to know. If anyone asked me while I was in my teens or twenties if I wanted to know who my birth mother was I would have vehemently said “no, of course not.” It took me over thirty years to realize what I needed to do. It is the adoptee’s dilemma of belonging and not-belonging, struggling between the need to know and misguided feelings of loyalty and gratitude. I can never forget the experience I had when I began my search for my mother over ten years ago. Before I found her I discovered that her brother was a Jesuit priest who had died rather young at Georgetown University. One day I got in the car and drove down to Georgetown. I visited my uncle’s grave and decided to ring the bell of the Jesuit residence. The priest who answered turned out to be not only my uncle’s classmate but his best friend, having grown up with him in Philadelphia. Fr. Dineen was a very kind man and I spent the entire day with him listening to the many stories he longed to tell of my uncle and their friendship. After dinner he invited me to his room, “to see some old photos,” he said. As we were about to open the album, it suddenly dawned on me that this would be the first time in my 33 years of life that I was to see someone related to me. Just last week I had a similar experience when I met with my mother’s roommate, Sophia, the roommate she was living with when carrying me. This was our third meeting since my mother’s death and Sophia said she had brought me a present. She took out a photograph she said she found accidently. It was a picture of both my mother and father, cheek to cheek, posing in one of those quick-picture booths. I secretly wondered as I studied their faces whether I was there too, still unseen, but forever a part of their lives. The losses suffered in adoption are also always there, whether we acknowledge them or not.

Those of you not adopted no doubt take for granted the importance of growing up with people related to you, who look and act like you. Adoptees miss that very primal experience. I would suggest it is at the heart of the dilemma of the adopted person who feels on some level that he does not belong in his adoptive family. This does not necessarily have anything to do with either the abundance of love within the adoptive family, or lack of it. It exists quite apart from the material well-being provided by the adoptive family. In adoption groups you often hear adoptees classify themselves as ‘good-adoptees’ or ‘bad-adoptees’. The good ones never searched while their parents were alive, the bad ones were always running away. But when the adopted person does decide to search, he is looking to belong. The adoptee feels himself to be a literal misfit, not quite fitting in, misplaced somehow, in another manner of speaking, he feels himself to be an exile. Belonging and identity are synonymous for the adoptee, but he must initiate his search, or at least acknowledge the desire to search for his identity, in order for the healing to begin.

A priest friend of mine once told me of his jarring experience when visiting a home for emotionally disturbed adolescents in Brooklyn. The priest walked into the home as a young man was singing the Irish ballad, Danny Boy. The young man had his back to the priest. When he finished the priest went over and tapped the young man on the shoulder, thanking him for such a beautiful rendition of the sad song. The young man quickly turned, revealing an Asian face. The priest instinctively laughed: “I’m sorry,” he said, “I thought you were Irish.” The boy’s eyes filled with tears and he angrily shouted back: “I am Irish, my name’s Michael O’Brien.”

The American Jesuit, John Courtney Murray, considered by many the greatest Catholic theologian America has yet produced, wrote this about identity: “Self-understanding is the necessary condition of a sense of self-identity and self-confidence…the peril is great. The complete loss of one’s identity is, with all propriety of theological definition, hell. In diminished forms it is insanity.” Let me repeat that important insight: “(t)he complete loss of one’s identity is, with all propriety of theological definition, hell. In diminished forms it is insanity.”

I suspect that everyone in this room today knows of Erik Erikson and his important contribution to the knowledge of human development by his investigation of developmental crises surrounding identity. Indeed, it was Erikson who invented the term “identity-crisis.” But I wonder how many know of his own experience of not-belonging.

“Erikson’s mother, a Danish Jew, never told Erik the true story of his origins, wanting him to believe that her husband, the pediatrician Theodor Homberger, was his father. As a boy growing up ‘blond, blue-eyed, and flagrantly tall’ in Germany, Erik thought it strange that his father was short and dark. He was acutely aware that he was referred to as a goy in his father’s temple, while to his schoolmates he was a Jew. He thought of himself as a ‘foundling’.” Erikson related this experience to Betty Jean Lifton which she recounts in her recent book Journey of the Adopted Self.

“Erik was in the Black Forest watching an old peasant woman milking a cow, when she looked up and said, ‘Do you know who your father is?’ He was taken by surprise. It was the first time anyone had said such a thing to him. He knew she must have noticed how different he looked from his father. Like Oedipus, he rushed to his mother to ask for the truth, (but) was given a half-truth. She admitted he had been adopted by Homberger, whom she married on the day Erik turned three. She spoke vaguely about having been abandoned by her former Danish-Jewish husband in Copenhagen while she was pregnant, and going to Germany to give birth. Sensing her discomfort, and responding to his own anxiety, Erikson submerged his need to know more about his father at that time. In his adolescence he would hear rumors that his father was not his mother’s former husband, but rather a Danish aristocrat whose name her brothers had sworn never to reveal. When Erik journeyed to America he renamed himself on his application for citizenship, calling himself Erik Erik-son. He had settled to create himself.” The search for identity and belonging can indeed be a very creative and fruitful process.

Names are an important aspect of the search to belong. Names are powerful and mysterious entities. My mother told me she named me, Thomas, for her brother the priest. The story of that most famous of adoptees, Moses, is given in the Book of Exodus. In Hebrew, however, the book is not called Exodus but rather the Book of Names. In it the divine name is revealed, the revelation of who God is. But it is also the story of who Moses is, a Hebrew raised Egyptian, and how his search to belong was pivotal to the history of salvation. “My name is Michael O’Brien,” the young Asian man defiantly asserted. “The complete loss of one’s identity is, with all propriety of theological definition, hell. In diminished forms it is insanity.” In the acknowledgment of the truth about Loss and the need to Belong a word must be said about Anger. The anger of the infertile couple at the loss of their dream: their intended children. The anger of the birth mother at the loss of her child: the relinquishment. In recent years we have seen, thank God, the anger of birth fathers whose rights are so often violated in the adoption process. And most significantly perhaps, the anger of the adopted person, who feels the extraordinary loss of parents, heritage and genetic connection.

For some adoptees, anger remains suppressed; for others, it becomes destructive and even violent. I can never forget the day I went to the Catholic Home Bureau in Manhattan to see if I could get any information regarding my adoption. The nun sat calmly behind the desk reading from the papers in front of her. She read me an account of my adoption and gave me the non-identifying information I had requested. I knew she was not supposed to tell me my mother’s name but I asked just the same. She said, of course, she could not give me the name but then asked in a tone of voice that triggered in me a cascade of rage: “Why would you want to know, didn’t you have a good adoption?” I realized that at that moment if I had had a gun I would have killed her. I am not exaggerating here, I know for certain I would have killed. Perhaps that’s what happened to Moses the day he saw the Egyptian beating the Hebrew, an event which triggered in him a cascade of rage, an anger that had been welling up all his life, intimately connected with his struggle over identity and belonging, and absolutely pivotal in the history of salvation.

Anger is a natural reaction to being hurt. Since adoption always involves loss for each member of the triad, and loss is a deep hurt, is it any wonder that there is a lot of anger permeating adoption. But anger can be a catalyst for positive change. In that great classic of western literature, The Odyssey, Homer gives us Odysseus, a man who is struggling to return to the place he belongs. Indeed the theme of the Odyssey could be summed up in one word: nostalgia, literally meaning, the pain for home. The etymology of words here is interesting. The root of nostalgia is nostos, meaning home. It is also the root of noos, which may be rendered, consciousness. At the end of the saga Odysseus confronts his enemy, Antinous, who was conspiring to rob Odysseus of wife, home and property while Odysseus was on his journey. The bloody scene in which Homer describes how Odysseus kills Antinous is quite powerful. And what does the name Antinous mean? It means anti-noos, against consciousness; Antinous stands for oblivion. It is Odysseus’ anger, his brutal rage, that enables him to slay Antinous. In this Odysseus rejects oblivion, that state of unawareness, and comes to consciousness – he regains home and family. Anger can be the catalyst which brings to consciousness the acknowledgment of the deep loss the adopted person has experienced, and so let him begin the healing process, his odyssey towards home.

A word of anger must be raised against what might be called the mark of illegitimacy. Society labels those born illegitimate, bastards. You may think it strange that I, as an illegitimately-born individual, am ambiguous about this designation. On the one hand I disdain the state and the church for creating such a designation because of its repercussions. In order for me to be ordained a priest I had to request special dispensation because bastards could not receive Holy Orders. That has recently changed but the psychological effects of such a designation always remain. On the other hand, it is argued that the closed adoption system was created to protect the child from the mark of illegitimacy. If that is true (though I am not convinced it is the real reason for sealed records) then I would prefer to be labeled a bastard and be able to see my birth certificate, than continue to be denied that fundamental right. In any event my parents were not married, and so I am born in different status. But I am in good company, and feel a certain kindred spirit with other bastards of history. And there are many: Erasmus, Leonardo da Vinci, Pope Clement VII, to name a few.

“I’ll tell you something,” a famous American once wrote a friend in strictest confidence, “I’ll tell you something, but keep it a secret while I live. My mother was a bastard, was the daughter of a nobleman so called of Virginia. My mother’s mother was poor and credulous, and she was shamefully taken advantage of by the man. My mother inherited his qualities and I hers. All that I am or hope ever to be I got from my mother, God bless her. Did you never notice that bastards are generally smarter, shrewder, and more intellectual than others? Is it because it is stolen?”

So wrote Abraham Lincoln of his mother Nancy Hanks. But there’s still more to the story. Lincoln always feared that his mother never properly married Thomas Lincoln. President Lincoln died before the marriage certificate he had requested years before had been found. It was discovered some years later, but some now think that document a forgery. And still, a further twist to Lincoln’s story. Many people, and according to his closest friend, even Lincoln himself, believed not only that Nancy Hanks never really married Thomas Lincoln, but that Thomas Lincoln was not his actual father. A few years back I was touring the South with a friend who was visiting from England. As we were visiting the home of Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy, I remarked to my friend that I couldn’t believe they had the gall to hang a picture of Abraham Lincoln in the hallway. The guide overheard me and said, “Oh, so many people say the same thing, but that’s not Lincoln, it’s Jefferson Davis.” The resemblance was uncanny, and indeed some believe that it was Samuel Davis who fathered both Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln. How does the radio commentator put it: “Now you know the rest of the story.”

I can’t fail to mention Jesus himself in this regard, because I believe Jesus knew the mark of illegitimacy. I think there is ample proof in the gospel texts to suggest that many believed Jesus to be a bastard, as is asserted in later Jewish apologetic works written to refute Christianity. For those of you who are Christian and have a hard time accepting the Virginal Conception, that is, the belief that Jesus’ father was God Himself, and so settle for accepting Joseph as Jesus’ real father, I would submit you are on shaky ground, because the gospels suggest, for some unmentioned reason, that it was obvious Joseph could not have been Jesus’ father. This poses a dilemma for the struggling believer: either Jesus was Son of God, or he was the bastard son of a Roman soldier as the later Jewish texts assert. In any event Jesus would have known what it felt like to bear the mark of illegitimacy.

A word of anger must also be raised against the closed adoption system and sealed records. Closed records, while purporting to insure confidentiality for the birth mother, mean that I as an adopted person have no right to my own name. Sealed records rob me of my name, my heritage, my medical history, and any connection to those related to me by blood. My question is this: Is the practice of closed adoption which separates child from mother without the child’s consent, which suppresses knowledge of family heritage and genetic connection, which refuses to reveal the child’s name even to the child himself, are these any different from the methods employed by the institution of slavery? Who can honestly deny that it constitutes, at the very least, a psychological slavery; or as Dr. Leston Havens of Harvard put it, “a psychological possession of the human being”?

And a word of anger must be raised against the myth of confidentiality. Lawyers, social workers and church officials assert that confidentiality was promised to the birth mother, and a promise given can not be breached. But then, I ask, why was my name, that is, the name given to me at birth by my birth mother, that is, my mother’s surname, why was that name printed on the very adoption papers given to my adoptive parents, if indeed the state wished to assure my birth mother of confidentiality? Why? Because confidentiality for the birth mother was not really ever intended. It is a myth.

When I testified some months ago before the New Jersey Legislature in favor of a bill to open records, the most vocal and powerful opponent was the New Jersey Catholic Conference, representing the Catholic Bishops of New Jersey. A word of anger must be raised against the hypocrisy of the Catholic Bishops of New Jersey who testified that the “dark secret” (these are their words not mine) the “dark secret” of the relinquished child’s birth must remain so because of the supposed confidentiality promised to the birth mother. Thus the bishops argue that a woman does indeed have a right to privacy from her own child. I wonder if Planned Parenthood and the abortion-rights’ movement realize they have such powerful allies in the Catholic Bishops of New Jersey?

Further, maintaining that “dark secret” permits church officials to release false baptismal certificates, misleading the adopted person either into believing he was baptized twice, or leading him to believe that the name he now uses is indeed his baptismal name, while in many cases it is not. How do church officials, particularly the Catholic Bishops of New Jersey, justify such hypocrisy and outright lies? All because a mother has a right to privacy from her own child, the bishops argue.

If the National Council for Adoption lobby gets its way, and the proposed Uniformed Adoptions Acts are legislated across this country, virtually anyone will be permitted to contract adoption with little or no supervision. Vacant wombs will be rented out, babies will continue to be contracted for, children bought and sold: all protected under the guise of confidentiality. The scenario of a Lisa Steinberg may not be the exception, but the rule.

The adoption reform movement has attempted over the years to correct what seems to many members of the triad a terrible injustice. I would suggest that the injustice of closed adoption is based on a philosophy of life we call dualism. Dualism sees everything in black and white; everything is reduced to an either/or dichotomy. This virus of dualism invaded the psychology of adoption early on, and remains active yet: “Psychology emphasized environment rather than heredity as a more important factor in child development,” Linda Burgess reminds us in her book The Art of Adoption. “Parents saw the chance to erase in their adopted children the hereditary components which, it was assumed, were of dubious quality…the personality and character of the child could be molded and their adopted children would become as if born to them.”

Today, as near daily discoveries are made in genetic research, we are coming to appreciate the great impact of heredity in human development, not only in its obvious physical results but in the psychological and even emotional temperament of the individual. And it becomes increasingly obvious that the human person is not the isolated product of either genetics or heredity, but rather the continuing result of a very complex interplay of inherited traits and environmental conditioning.

Dualist thinking invades our religious life and beliefs about human life. It undermines the proper relationship between body and soul, spirit and flesh. It distorts our vision and teaches us to disdain the body. It abhors the flesh; it loathes things sexual. And if adoption is about anything, it is about sex, about the uncontrollable urges of first love, or even the violent urges of adolescence. Dualist thinking teaches us to regard everything in the adoptees’ history prior to the adoption as dark and dirty, to be forgotten and purged. Dualism is the preeminent denier of truth. True religion on the other hand seeks to embrace the tension between body and soul, spirit and flesh. Religion, according to the great Catholic theologian von Balthasar, is “the renewed bonding of previously separated parts.” St. Teresa of Avila, the great Spanish mystic, put it this way: “For never, however exalted the soul may be, is anything else more fitting than self-knowledge…” The adopted person’s search for his origins is then a religious experience. It is a spiritual journey, a pilgrimage of self-knowledge, a holy endeavor.

The search is undergone in order to gain the experience of integrity, of wholeness, of health. The Latin root of the word salvation is salus, meaning health. And the English words wholeness and holiness are more closely related than simply their shared sound. In the adopted person’s search for origins, in his drive for the truth, and through his desire to belong, he becomes the paradigm, the sacrament if you will, of Everyman. “You have made us for Thyself, O Lord,” St. Augustine wrote some 1500 years ago, ” and our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee.”

Malcolm Muggeridge, the British journalist turned Christian, wrote in his memoirs: “the first thing I concluded about the world – and I pray it may be the last – is that I was a stranger in it…For me,” Muggeridge said, “there has always been – and I count it the greatest of blessings – a window that never finally blacked out, a light never finally extinguished. Days or weeks or months might pass. Would it never return – the lostness? I strain my ears to hear it, like distant music; my eyes to see it, a very bright light far away. Has it gone forever? And then – ah! the relief. Like slipping away from a sleeping embrace, silently shutting the door behind one, tiptoeing off in the gray light of dawn – a stranger again. The only ultimate disaster that can befall us, I have come to realize, is to feel ourselves at home here on earth…”

Walker Percy, another Catholic writer, touches on this parallel feeling of belonging and not-belonging in his novel The Moviegoer. It is a story about a man who is searching for meaning in life. It takes place in 1960 or so in New Orleans over the course of the week which ends on Ash Wednesday. Near the end of the novel the main character is sitting with a friend in his car in front of a church. He notices a car driven by a black man pull up behind them. “A florid new Mercury pulls up behind us and a Negro gets out and goes into the church. He is more respectable than respectable; he is more middle-class than one could believe: his Archie Moore mustache, the way he turns and, seeing us see him, casts a weather eye at the sky; the way he plucks a handkerchief out of his rear pocket with a flurry of his coattail and blows his nose in a magic placative gesture (as if to say ‘you see, I’ve been here before, it’s a routine matter)…

(Later) he has come outside. His forehead is an ambiguous sienna color…it is impossible to be sure that he received ashes. When he gets in his Mercury, he does not leave immediately but sits looking down at something on the seat beside him. A sample case? An insurance manual? I watch him closely in the rearview mirror. It is impossible to say why he is here. Is it part and parcel of the complex business of coming up in the world? Or is it because he believes that God himself is present here at the corner of Elysian Fields and Bons Enfants? Or is he here for both reasons: through some dim, dazzling trick of grace, coming for one and receiving the other as God’s own importunate bonus? It is impossible to say.”

“We shall not cease from exploration,” T.S. Eliot mused,

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

When an adopted person is permitted and encouraged to search for his genetic connections, for his origins, a paradox occurs: he may well end up realizing that he rightfully belongs in two places, that he does indeed have two sets of parents.

I began this presentation with a simple cinematic image, permit me to end with another from the film Empire of the Sun. It’s about a British boy who is living in Shanghai with his parents when the Japanese are about to invade. In the mass confusion of the Europeans’ exodus, the boy is separated from his parents, and spends his adolescence in a prisoner of war camp. It is the last scene of the movie which strikes a deep resonance within me. The war is over and parents of lost children have come to the Red Cross camp in the hope of finding their lost children. We see a group of youngsters huddled in a circle, adults moving slowly through them, desperate to find their missing children. The boy’s father passes without recognizing him. His mother does the same, but then returns and studies the boy’s haggard, weary face, and then she calls his name. The camera first focuses on the boy’s face, then fixes solely on his eyes. The boy is so tired, he cannot even blink, he seems catatonic, his glassy eyes the windows to a worn and weary soul. The boy’s mother embraces him. Then, and only then, the creased wrinkles around those eyes begin to relax and the boy finally, gratefully, slowly closes his eyes. The wandering, the worrying, the searching, is at an end. I wonder if this is what St. Augustine meant when he said “our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee.” I wonder if this is what that ancient prayer for the dead is meant to convey when we pray at burial: “Eternal rest grant unto them O Lord…”

And so permit me to conclude with a prayerful invocation of sorts, a plea to the Patron Saint of this beautiful city, St Anthony of Padua. By what trick of grace are we all here today, I wonder, because you know St. Anthony is the Patron Saint of both the barren and the pregnant. Strengthening adoptive families is about acknowledging the permanence of infertility and the responsibility of an unwanted pregnancy.

And St. Anthony is, as all Catholics know, the founder of things lost. My father is sadly now in the beginning stages of Alzheimer’s and I try to sleep at their house often. The other night I got up early to leave and discovered my car keys missing. I realized that my father had taken them and would not remember where he put them. My mother said: “say a quick prayer to St. Anthony,” which I did just as my father picked up something on the counter and there the keys were.

Coming to San Antonio has been an especially good experience for me because my cousin and his family live here. My cousin and his wife have been under a great deal of stress these last few days because their teenage daughter ran away. I felt so badly for them but I really didn’t know what to do until I visited the Cathedral of San Fernando yesterday and saw a statue of St. Anthony. I lit a candle and asked St. Anthony to find my cousin’s daughter. That very afternoon my cousin called to tell me that they found their daughter at a friend’s house safe and sound. St. Anthony, founder of the lost, can be a powerful ally to those of us who know what it means to lose something or someone. Strengthening adoptive families is about the acknowledgment of loss, the loss of children, the loss of parents, the loss of one’s heritage and genetic connection.

St. Anthony is often pictured holding the Christ child in loving adoration. He adores Jesus as both divine and human, holding the tension of Jesus’ true identity, his dual nature, without sacrificing the importance of one for the other. St. Anthony does not settle for an either/or solution. Perhaps St. Anthony is after all the best guide we could have to help us reject that dualism which forces us to think of adoption as an either/or dichotomy, having to choose between environment and heredity, and help us to embrace the creative tension found in each adopted person.

For in the adopted person is found a disquieting paradox that reminds all of us we are truly orphans. Adoption plays a mysterious trick on us, but I believe it a trick of grace. In the adopted person one may very well find the ground-of-being where sex and love have intercoursed; the sacrament, if you will, of the fusion of nature and grace.

Thank you for your kind attention.

(Note: Father Brosnan left the podium to thunderous and prolonged applause. His presentation was a common topic of conversations for the remainder of the conference. – Bill Betzen.)

This article originally found here: http://openadoption.org/gladney/index.htm

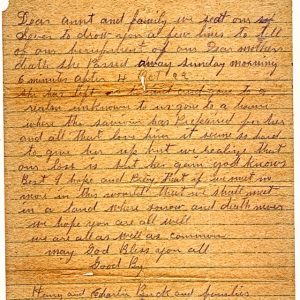

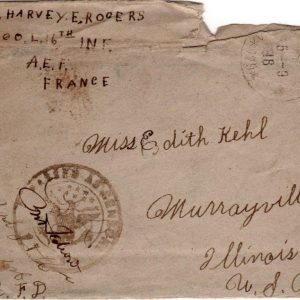

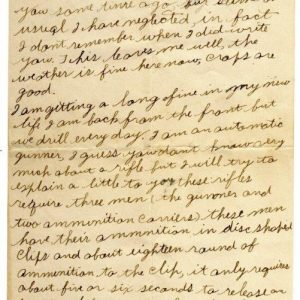

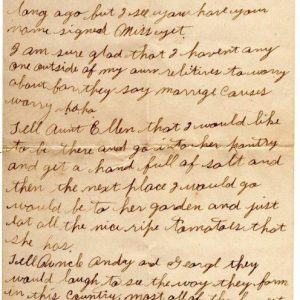

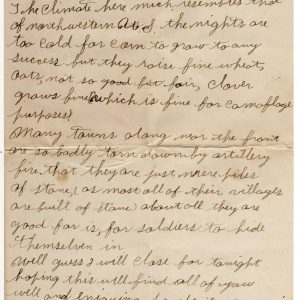

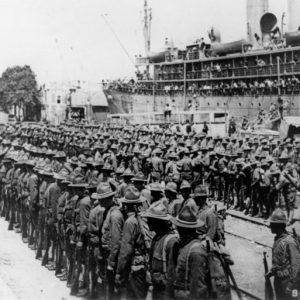

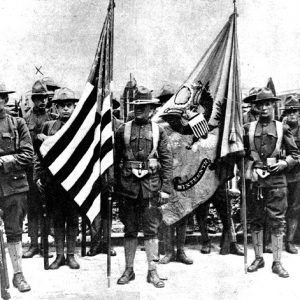

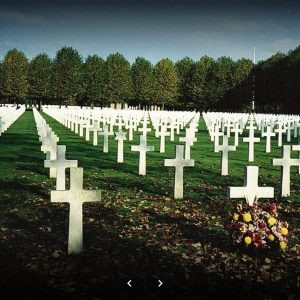

Armistice Day was established to honor the day peace finally arrived – Nov. 11, 1918, ending World War I. On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the guns fell silent. It brought an end to four years of war which crippled Europe and left 17 million dead. This is the story of how WWI touched our little family.

Armistice Day was established to honor the day peace finally arrived – Nov. 11, 1918, ending World War I. On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the guns fell silent. It brought an end to four years of war which crippled Europe and left 17 million dead. This is the story of how WWI touched our little family.

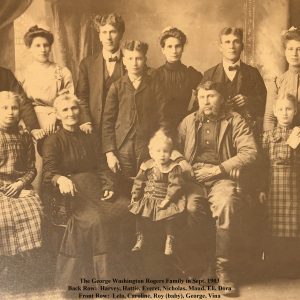

THE STORY TELLERS

THE STORY TELLERS